by Abbot Fletcher for Points East magazine

The sailing life began for me on a small sailboat that my father had rented in Coronado, California in 1929. But it wasn’t long before I had discovered the Gulf of Maine.

In the early 1930s, I sailed and raced with my grandfather on Casco Bay, Maine aboard his 32 foot sloop Juanona – at least I did when I wasn’t sailing smaller boats with other kids.

The summers of 1937 and 1938 were spent on the 33 foot Herreshoff sloop Laura in Newport, R.I., watching the cup races and racing about Narragansett Bay with my father. During those two summers, when I was 15 and 16 and sailed with younger siblings and neighborhood kids, the only restriction my father put on me was not to go out of sight of the Brenton Reef Lightship.

But the 1938 hurricane destroyed Laura, so my sailing and racing reverted to Juanona, which my grandfather, approaching 90, turned over to me. After the interruption of the World War II years and with long weekend commutes from New Jersey to Maine, my wife and I decided we would live in Maine even if I had to dig ditches. And thus in 1953 our affair with the coast of Maine began.

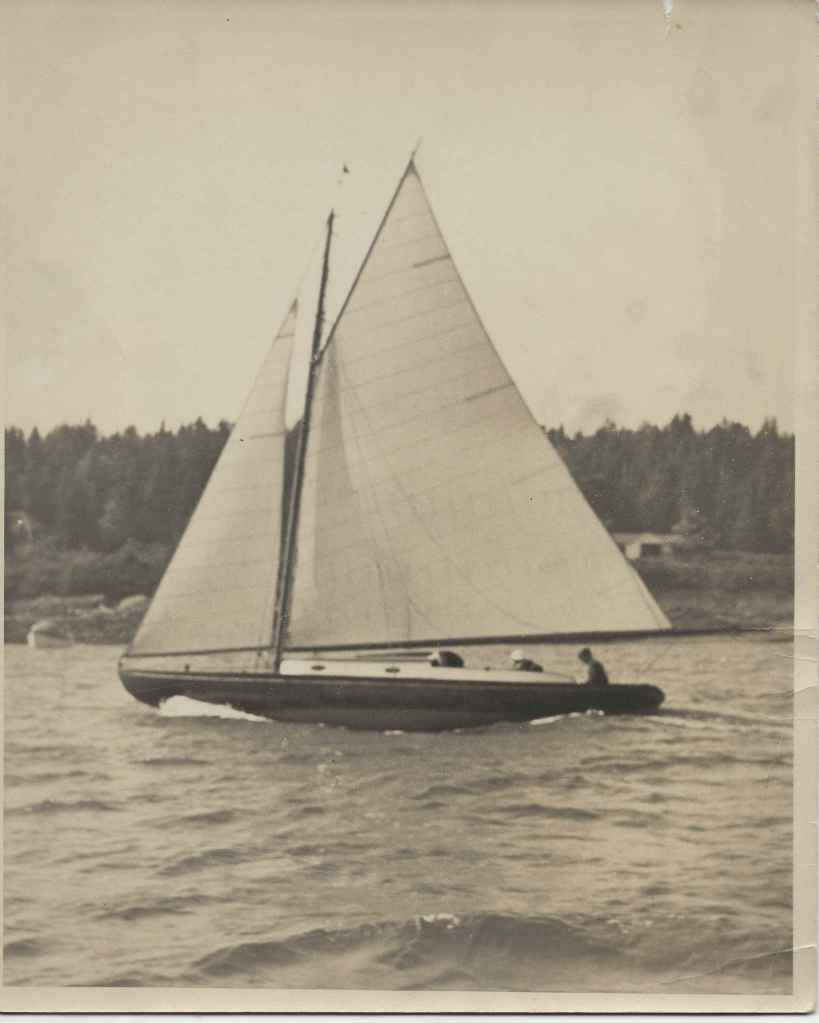

Two summer cruises with an older cruising couple opened our eyes to the beauty of Maine’s rockbound coast, to fog navigation and to snug harbors. With Juanona now more than 60 years old, I replaced her with a 38 foot Tripp Javelin. My children chose to name the boat Majek after the family names of Max, Abbot, Judy, Eileen, and Kristin.

With family and friends we day-sailed and raced her, and during my two-week vacations cruised the coast of Maine and to Rhode Island to show off the new boat to old friends and relatives. We sailed overnight from Casco Bay to the Cape Cod Canal, arriving at the canal in the first daylight for the canal transit and the final leg to Rhode Island or Martha’s Vineyard or Nantucket. Even daughter Krissy, not yet 10, took her turn steering half-hour tricks.

In East Penobscot Bay the three kids for the first time set the spinnaker by themselves.

Majek’s first years of racing grew quickly into the Gulf of Maine Ocean Racing Circuit (GMORC), with races all the way from the Kollegewidgwok Yacht Club at Blue Hill to Kittery. Some summers there were six weekends of overnight races and two of day races. Getting the boat moved from one yacht club to another was a major challenge.

I was fortunate to have my kids, and sometimes my wife, to move Majek between yacht clubs. Since my father and grandfather had me as a kid sailing sizeable boats on my own, it was my goal to do likewise with my children. Judy, Max and Krissy took Majek out as teenagers. They moved her up and down the coast, including in fog and rain.

In an early Monhegan race, with the men at 2 AM tuckered out at the Manana whistler, 12-year-old Max steered while Judy, 15, navigated. I told her to watch for other boats and let me know when we got near Bantam Rock. After several inquiries she told me we had passed Bantam Rock and to go back to sleep.

Majek’s crews in the GMORC had many pleasant and fun weekend evenings at the Arundel, Portland, Harraseeket, Boothbay, Camden and Castine Yacht Clubs. In a race when an unfamiliar boat squeezed Majek out at the starting line, backwinded her or starboard tacked her, I said to myself, “There’s a bad guy to be regarded with suspicion.”

In the subsequent cocktail party, I got to know that “bad” guy. Over the years, with no exceptions, we gained a lifelong wonderful group of friends along the coast of Maine. We also gained an appreciation for the unique challenges facing cruising and racing sailors in the Gulf of Maine.

Racing among the islands of Maine has a whole set of variables critical to doing well. Current is a major factor, especially in light air, such as tacking out of Hussey Sound in a counter-current. The wind variable around the islands is also a critical factor, such as the draw down the west side of Damariscove Island or at times close in down the east side of Isleboro.

During one race, as I watched the afternoon sun beat against the rocky cliffs of Cape Rosier, I figured the warm air would rise and draw the light southwest wind under it. So we headed in close to the cape and watched the rest of the fleet sail by farther out, heading for the finish line at Castine. A local sailor laughed when he told me that evening that that was a well-known “dead spot.”

A wind phenomenon not fully recognized is the afternoon descending southwester on the leeward side of many islands, such as Seguin and North Haven.

In a Boothbay regatta, with Majek two-thirds of the way back and the fleet all headed north of Fisherman’s Island and a daughter screaming at me, Majek separated from the pack and headed through the passage between Damariscove and Fisherman’s Islands. We picked up the descending southwestern, filled the spinnaker as the knot meter climbed from 2 to 5.5 knots, and were first around the next mark east of Fisherman Passage – with an apology from the daughter.

In sailboat racing, there is a “pack” psychology such that if after rounding the windward mark the lead boat sails above the rhumb line for boat speed, everybody astern follows. One of Majek’s philosophies is to find advantageous opportunities and separate from the pack. Most of the time this has worked, but a few times it has been a disaster.

In a Camden-Castine race in very light air, in which Majek is a dud, the fleet close-reached for better boat speed toward Isleboro. Majek, following behind and with both daughters screaming at me this time, broad reached along the west side of the bay and north of Lincolnville picked up close to shore a good wind draw. Majek converged with the fleet and eventually caught up with the leaders. More apologies.

Separating from the pack has also been a philosophy of life that I have used and that I have tried to instill in my children and other young people.

The Monhegan-Manana races have been a favorite of Majek, which has now competed in 32 of them, winning her class 11 times. After an earlier Monhegan race, when Majek had finished well down the list, Max kept hounding me that I did not tack when he told me to and I went inshore when he told me to go offshore. When I could take his criticism no longer, I told him that, unfortunately, he could not choose who his father was.

Krissy grew up as Max’s little helper on Majek’s foredeck, setting spinnakers and changing jibs. When Max took off for the Caribbean and the Pacific Ocean in a Westsail 32, teen-aged Krissy took over the foredeck. Once as we approached the windward race mark at Cape Porpoise, I hollered to her, “Don’t forget the downhaul at the end of the spinnaker pole!”

“You steer,” she hollered back. “I’ll take care of the foredeck.” That ended the conversation and the spinnaker blossomed beautifully.

Later, when I had business commitments and could not participate in the Monhegan Race, I made an offer to Majek’s crew of Max, Judy, Krissy, Judy’s husband Doug, Bruce Washburn and Jim Bennett. “If you win,” I said, “name your bottle.” Monday night I got a long-distance call from Krissy with a list of the six most expensive bottles they could find – $96 worth. She didn’t mention how they did in the race.

(Kris Fletcher, Doug Woodbury, Max Fletcher, Jim Bennett, Bruce Washburn, Judy Fletcher)

Cruising Majek

Majek’s cruising has extended from the Saint John River to Mystic, Conn. It is easy to name 160 harbors and coves where Majek has spent the night. Favorites include Grand Manan Island, Cutler, Cape Split, the Cow Yard on Head Harbor Island, and the Mud Hole on Great Wass Island.

Common practice for a limited vacation period has been to make two or three long day’s runs down east and then work back toward home. With the Maine coast’s light winds, it is better sailing when tacking and reaching back. And tacking among Maine’s lovely islands gives one much more closeness and intimacy to shorelines and woods and ospreys and seals and even a few eagles.

Finally, if fog or foul weather slow or stop progress, you are not such a long way from home.

A few favorite areas include the area around Vinalhaven, such as in Seal Bay as far in as you can go, the islands north of North Haven, all around Isle au Haut, and the Jonesport area. It takes a lifetime to get to know and experience all of the interesting places.

Though most of sailing the coast of Maine is lovely blue days, fog is a factor to be reckoned with. Though modern electronic devices are a great help, in short runs in protected waters the old-fashioned methods, such as compass-course timed runs to buoys, noise makers and bold shores, are best.

Focusing on instruments is no substitute for paying attention to noises and waved action and smells and to other boats going by. In close-in fog runs we put one person forward (or two talkative crew members) as lookouts and one person on the helm to steer compass courses.

The navigator with charts and the timer calls the courses and tells the lookouts what to look for and when.

Years ago before Loran we were cruising Majek along the south coast of Campobello Island in the fog and strong Bay of Fundy current.

As time went by I knew less and less about where we were and said to myself, “What in the h… are we doing out here lost with three little kids?” I could still hear the West Quoddy Head fog horn five miles away, so I picked a 30-degree safe sector and headed back toward West Quoddy Head lighthouse in the center of the 30-degree sector. The fog horn got louder and louder until all of a sudden we could see the light at a surprisingly high elevation directly ahead. We altered course into Quoddy Roads and a safe anchorage until the fog cleared.

On another occasion in a particularly foggy summer, my wife and I rode Majek up the Penobscot River to Bangor on an incoming tide and rode back on the outgoing tide, getting a view of logging relics.

Cruising and racing the Gulf of Maine has provided adventure and camaraderie; it has stretched the spirit; it has been miserably cold and wet at times, scary at other times, tedious at other times; it has helped children grow up and learn about the world and about responsibility; and of course it has offered lovely blue days out on the water among the beautiful islands.

It has all been relished fun.

Postscript: Learning to live – and win – with a boat’s weaknesses

Majek has participated in 230-plus races with 80-plus first places. In 1993 Majek shifted her emphasis and participated in the Marion-Bermuda Race, with a first in class and third in fleet, and in 1995 Majek was third in class and third in fleet. In 1997, in the Marion-Bermuda race, Majek was first in class and first in fleet and in the Marblehead-Halifax Race was fifth in the fleet.

Majek’s win in the Bermuda Race has caused some reflection on the factors that led to her success. Crews, not boats, win races. Winning races is one-third sailing fast and two-thirds tactical choices.

We learned to avoid Majek’s disastrous racing weaknesses. Her high wetted surface makes her a dud in light air; her rudder is well forward, requiring much helm turning in light air and rough seas; her sharp bow causes speed-killing pitching in certain wave conditions.

In 1980, we modified Majek’s rig by moving the center of effort one foot forward to better balance the helm. We also increased the rig height five feet so Majek would be less of a dud in light air.

Majek’s win in the 1997 Marion-Bermuda Race was due to her able crew of navigator Max, Bruce Washburn, Jim Bennett, David Skaling, Henry McAvoy, and myself. We sailed the boat fast with focused helmsmanship, good sail shape and trim, and fast responses on sail adjustments.

Southeast of the Gulf Stream, when a stormy front came through with winds all over the place, the crew winged the jib out and shifted it to the other side and back again with each wind shift so that we got all the boat speed possible.

We used the favorable side of Max’s projection of a clockwise warm eddy and then crossed the irregular Gulf Stream where, if it wouldn’t help us, it would hurt us the least. At this point we started to sail close-hauled in a chop to head for the favorable side of a cold counter-clockwise eddy.

Recognizing that this was a disastrous choice for Majek, we altered course still not too far from a rhumb-line course, to loop around the counter-current side of the cold eddy. The tactic sped us up as we took advantage of a veering wind for the next day and a half, doing what Majek does well – close reaching. This was perhaps the major tactical choice of several good tactical choices and two not-so-good choices.

Winning the Marion-Bermuda race, with its many challenging variables, was the most exhilarating of our many racing efforts.

Abbot Fletcher