The enigma of the Southern Ocean invaded my mind, urging me to abandon a circumnavigation in midstream and return to Maine the hard way – around Cape Horn. Christopher Robin, my Westsail 32, had been my home for 13,000 miles from Maine across the Pacific to New Zealand. I’d seen magnificent places, sweated through tricky landfalls, and come to know the romance of South Pacific cruising. But now the prospect of continuing the circumnavigation through the trade-wind belts paled in comparison to a new alternative: simply head southeast from New Zealand rather than northwest. The Southern Ocean was so close. I thought of the words of the British voyager and mountaineer H.W. Tilman: “There is little point in setting out for a place one is certain to reach.” I was certain, within reason, of reaching South Africa and the Cape of Good Hope. But Cape Horn? Maybe. The Southern Ocean appealed to some basic instinct. I longed to experience the unknown on a raw level. It was all so simple: Head southeast from New Zealand and peel away a page of the unknown.

Finding the missing part of the equation clinched the decision for me: It was Canadian Rob Andrews, whom I’d come to know while he had been skipper of a Swan 65. Rob proved to have a rare combination of sailing talent, good-natured disposition, calmness in the face of adversity, and adaptability. He also shared my desire to see Cape Horn first-hand from the deck of a small boat. It took us one December weekend in New Zealand pubs to decide to begin preparations.

Our first challenge was to convert an ocean cruiser into a vessel capable (we hoped) of withstanding anything that would come our way, and to do so before the southern summer passed us by. It was already mid-December; according to the best advice, we should leave immediately in order to reach the Horn in time to avoid the onset of autumn gales. We set a departure deadline of January 9 and began a feverish schedule to ready the boat.

To beef up Christopher Robin we covered all hatches with permanent, through-bolted plywood and aluminum covers and bolted a piece of 1-inch-thick Lexan across the companionway. It would require some gymnastics to get by, but it strengthened an obvious weak point. We added a second compression post under the deck-stepped mast, replaced all standing rigging, and built up the spreader bases. A spare steering-vane oar was fabricated, along with a pair of warps, and attached to the hull with chain to prevent chafe. A sailmaker carefully inspected all sails and added two new storm jibs of different sizes to our inventory.

We relied on Rob’s experience cruising Alaskan waters to choose warm clothing and on our combined sailing experience to find high energy, easy-to-prepare foods. We stripped supermarket shelves bare of nuts, candy bars, dried foods, and cheeses. A cruising friend canned two dozen jars of curried lamb and beef bourguignon for us.

Departure day arrived, along with the customs man. It felt strange to write “Falkland Islands” on the clearance form. Sydney, yes. Suva, yes. Stanley? I might as well have written “the moon.” What we were embarking on seemed beyond comprehension, particularly since the idea had been seriously brought up only four weeks before. But leave we did, after an all-nighter of parties, stowing our fresh supplies, and some teary phone calls home.

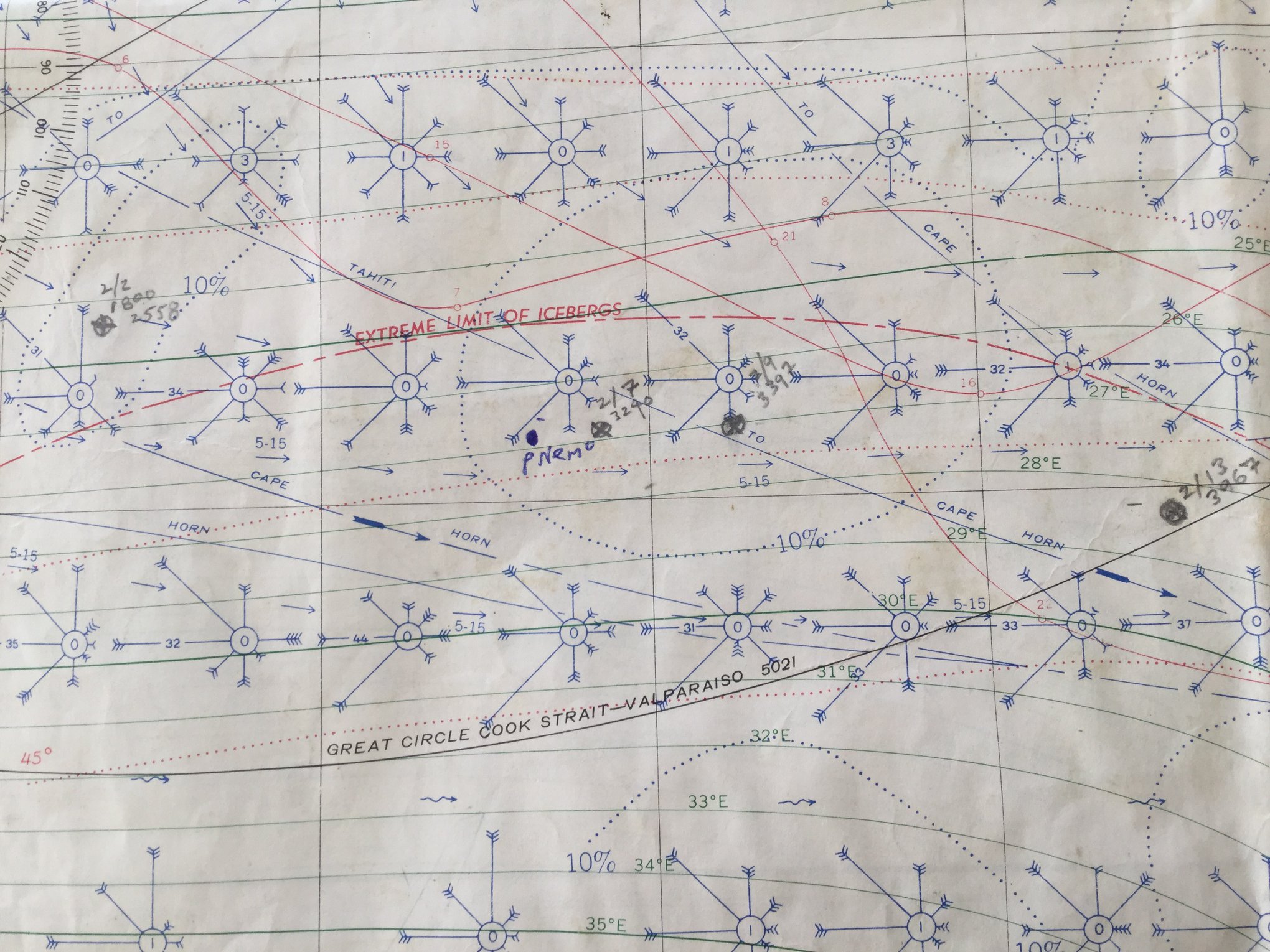

With a long sail ahead of us, and already late in the season, we hoped to get a fast jump by heading straight for 45 degrees south and the prevailing westerlies. After a month of anticipation, we looked forward to finding out exactly what the fabled Southern Ocean was all about. Barely out of the starting gate, we got stopped cold. On January 14, only 600 miles out, the wind came around to the southeast, and three days later these headwinds were blowing a steady Force 8, 35 to 40 knots. The pilot charts, which indicated winds blew less than 7 percent of the time from this quadrant, unjustly received more abuse than they deserved from us, for we were not in a normal weather pattern. Green seas swept the foredeck. Our storm jibs and trysail were stretched taut as steel. Christopher Robin struggled for every mile.

By January 18 the gale was gusting to Force 9 to 10, and our effective progress was nil. We decided to heave to and give the boat and ourselves a rest. Soothing music from the cassette player became more a reminder of the peaceful, shore side life we had left behind than any significant comfort against the elements raging outside.

That night Rob and I snoozed in our bunks, trying to relax despite the shrieking. Christopher Robin rode on a 20-degree heel, giving way to each oncoming wave like a boxer giving just enough to soften each blow. But at 0330 Christopher Robin took one square on the chin. I was awakened by a tremendous roar, felt myself pressed against the underside of the deck, and heard water pouring in below. We had been rolled past 130 degrees, and the sea had poured through a 4-inch gap in the companionway hatch, which had been left open for ventilation. In the darkness I pumped the bilge and listened carefully to hear the electric pump shut itself off. We were not taking on any water. I grabbed the flashlight and poked my head out. The mast, with its small storm jib lashed to windward, stood intact. Christopher Robin had survived Round One. A pair of jokers, discarded from a new deck of cards the day before, had wedged themselves in the ceiling trim while the boat was upside-down, a sardonic comment on our efforts.

Rob and I assessed our situation. We were 10 days out and were already beginning to feel thoroughly beaten up. In 10 days we’d covered less than 800 miles, and we hadn’t yet reached 40 degrees south, where we expected the real rough stuff to start. And yet, the four days of gale-force headwinds, along with the knowledge that we’d survived a severe knockdown intact, gave us a renewed sense of determination, almost defiance. We knew the rules of the game were going to be a far cry from the trade-wind sailing we’d been accustomed to, and we resolved to buckle down and accept the Southern Ocean on its terms.

Two days later the wind finally veered to the north of east and eventually carried on around to north and northwest. We scooted down to 45 degrees south to get ourselves square in the westerlies and began romping eastward.

After a couple of weeks at sea, with another five or so to go, I was pleased to find myself settling completely into a timeless dimension. I’d made the important psychological adjustment whereby I no longer tallied up how long we’d been out or how much longer we had to go. We paid little attention to time. In other than heavy weather, watch schedules were flexible. If I was into a good book, I’d let Rob sleep. Without even discussing it, we instinctively made sure we each got plenty of rest. We covered for each other without rigid schedules or appointed chores. Since we were each willing to do more than our share, this arrangement worked beautifully-perhaps because underneath we knew that ultimately our lives were intertwined, each of us dependent on the well-being of the other.

We’d been given, upon leaving New Zealand, a stew for our first night at sea. The chefs never suspected that the stew would take on a life of its own. Each night Rob and I added items; beef, lamb, ham, salami, every type of vegetable aboard, and a smorgasbord of spices found their way into the pot. We always added enough new ingredients so there’d be a base left over for the following night. There was never any argument over what was for dinner, nor any need to clean the pressure cooker after a meal. On the twenty-fourth, spooning up our fifteenth consecutive stew, Rob and I simultaneously looked up from our bowls. No words needed to be spoken. I emptied every last drop of stew overboard while Rob foraged around to find out what else we’d brought along.

By the end of January, after three weeks at sea, we’d grown accustomed to and confident in our new surroundings. We’d endured a series of gales as low-pressure systems to our south danced around the globe. With each gale we learned which sail combinations worked, how best to position the boat relative to each sea, and how to pace ourselves mentally and physically in order to keep our concentration at a peak. Only one wave taken wrongly could ruin our voyage, and thus our focus during each gale came down to each individual wave – wave after wave, minute after minute, hour after hour. “This is where we earn our pay,” I thought.

Our bodies gradually adapted to the cooler air and water temperatures, both of which averaged in the low forties (Fahrenheit). We typically wore three layers of clothing over our legs and five over our torsos. Wool hats stayed on 24 hours a day. When I could ignore the state of cleanliness of my clothes and body no longer, I would brace myself for a seawater sponge-down, along with a full-head dunking in a bucket to wash my hair. Then I’d wash my long johns in a bucket. This alone chilled my hands to the bone, and I’d then do my best to rinse out the salt in a cupful or two of our precious fresh water.

On February 7 we sailed over “Point Nemo”, the spot on the globe furthest from any land. Through SSB radio nets we knew of a single-handed Belgian sailor named Mick a couple hundred miles away, en route from Sydney to the Canary Islands. We surmised that the three of us may well be the most isolated humans on the planet.

It took us a month at sea to approach 110 degrees west and begin easing south to make our descent to Cape Horn. Crossing the fiftieth parallel was a transition, a commitment from which there would be no turning back. Our senses heightened, we checked the barometer more frequently, and each increase in wind speed or wave height was registered and scrutinized in our minds. We had 1,600 miles to go to Cape Horn, and we knew that all we had ever learned, all we had lived for, had come together at this time and in this place.

On February 9 the seas began building from the west, accompanied by a falling barometer and a rising wind. When the waves began to break violently, Rob and I began began a 2-hour-on, 2-hour-off rotation of steering by hand. Our windvane could not anticipate the seas; it could only react after a change in wind direction, and we could not afford to let one of these monsters slew Christopher Robin sideways under its foaming crest. When the wind built to Force 9 we decided to get out our smallest storm jib – a 36-square-footer. Two quick pulls on the halyard and it was up, and Rob and I howled when we first saw its diminutive size. Twelve hours later we were no longer howling. The wind was howling, and we were hanging on while averaging 6 knots and surfing at over 10 knots down the face of 30- to 40-foot seas.

On the morning of February 11 our little jib – half the size of a sailboard sail-was overpowering the boat in frequent squalls, pulling us down the swells at reckless speeds. We took the sail in and nonetheless averaged 5 to 6 knots, surfing regularly to 8, 9, or 10 knots.

Rob and I found new internal sources of energy. We’d been steering by hand, on 2-hour watches, for 48 hours, and still the gale raged on. For 2 hours the helmsman had one thing to think of: keep Christopher Robin nearly square to the oncoming wave. At night all was black, heightening the sense of the wind against your helmet, the cold sinking into your clothing, and the feel of each wave as it swelled up under the hull. Sometimes a wave would slap aboard onto your face, to begin anew a cold drying of the skin. Wave after wave, you stamped your feet to keep circulation going, concentrating on the inescapable present; then came momentary relief at managing to get over the wave just passed before you had to deal with the next coming up astern. Then your nearly forgotten visual ease would be awakened by the shadows of a soft light turned on below, the mere sight of which stirred a feeling of inner warmth. Ten more minutes, 15 at most, and your god blessed mate would be up to relieve you at the helm. I wondered that anyone would want to trade places with me, much less as promptly and cheerfully as Rob unfailingly did.

“The weather seems to be getting worse,” we would say coming on. “I think it’s easing up, actually,” would reply the man on watch, who’d had 2 hours to grow accustomed to the fury.

And then you gave up the tiller and took one last look around and felt one last twinge of sympathy for leaving your mate under such wretched conditions. You climbed below, grabbed the Thermos, poured a cup of tea without spilling any. Drink it right down-don’t worry about the burn on your lips. Grab a towel-only a damp one left-and wipe down your face and hair. Hang up the wet-weather gear, set the alarm clock for 1 hour, and climb into that sleeping bag while it still holds some warmth. Nothing you can do now. Sleep.

One minute later, the alarm clock beeps. Up. Up. Don’t be a minute late relieving Rob on deck, for you know just how chilled he is. Another cup of hot tea. Hand up half a chocolate bar, wolf the other half down yourself. Pull on your cold, raw wet-weather gear. Poke your head out the hatch, hesitate just a moment to soak in the relative calm and warmth of the cabin, and then out you go into the elements.

The afternoon of February 12 the sun came out in near-cloudless skies, sparkling the breakers, glistening against the mountains of water tumbling over themselves. We were still running under bare poles, making 130-mile days. I sat in the cockpit, feet braced, arms wrapped around the tiller to guide us down the swells. Dressed like a doughboy, looking through salt-caked sunglasses, I laughed to imagine what the albatross roaming overhead thought of this strange animal surfing along below them. In spite of, or perhaps because of, the howling wind and thundering seas, I knew that one day I would look back and think of this as one of the happiest days of my life.

Yet as our mileage to Cape Horn diminished, an underlying foreboding increased. We now had 1,300 miles to go, farther south into the nether reaches of the globe, and if the seas could be this large here, how much bigger could they get? How much more could Christopher Robin handle? “There is a feeling we are sitting on a time bomb,” I wrote on February 19, “and every time the barometer changes (which it does a lot) I think, this is it. We fully expect to get hammered at least once more.” Yet the days went by, and every day we put another 120 to 140 miles behind us – miles that couldn’t be taken away.

On February 23, following two stormy days, the wind moderated and a perfect double rainbow formed directly ahead of us, as though we were about to pass under a colorful arch. “Come this way under the rainbow, Christopher Robin.”

The next day the seas were quiet, and we felt safe in crossing onto the continental shelf. We’d seen not a trace of land or civilization for 47 days, and now the simple act of turning on the depth sounder and seeing it register 75 fathoms felt as heartwarming as if we were safely in port. At 1730 the island of Diego Ramirez appeared to our south, a forlorn-looking place in the Drake Passage.

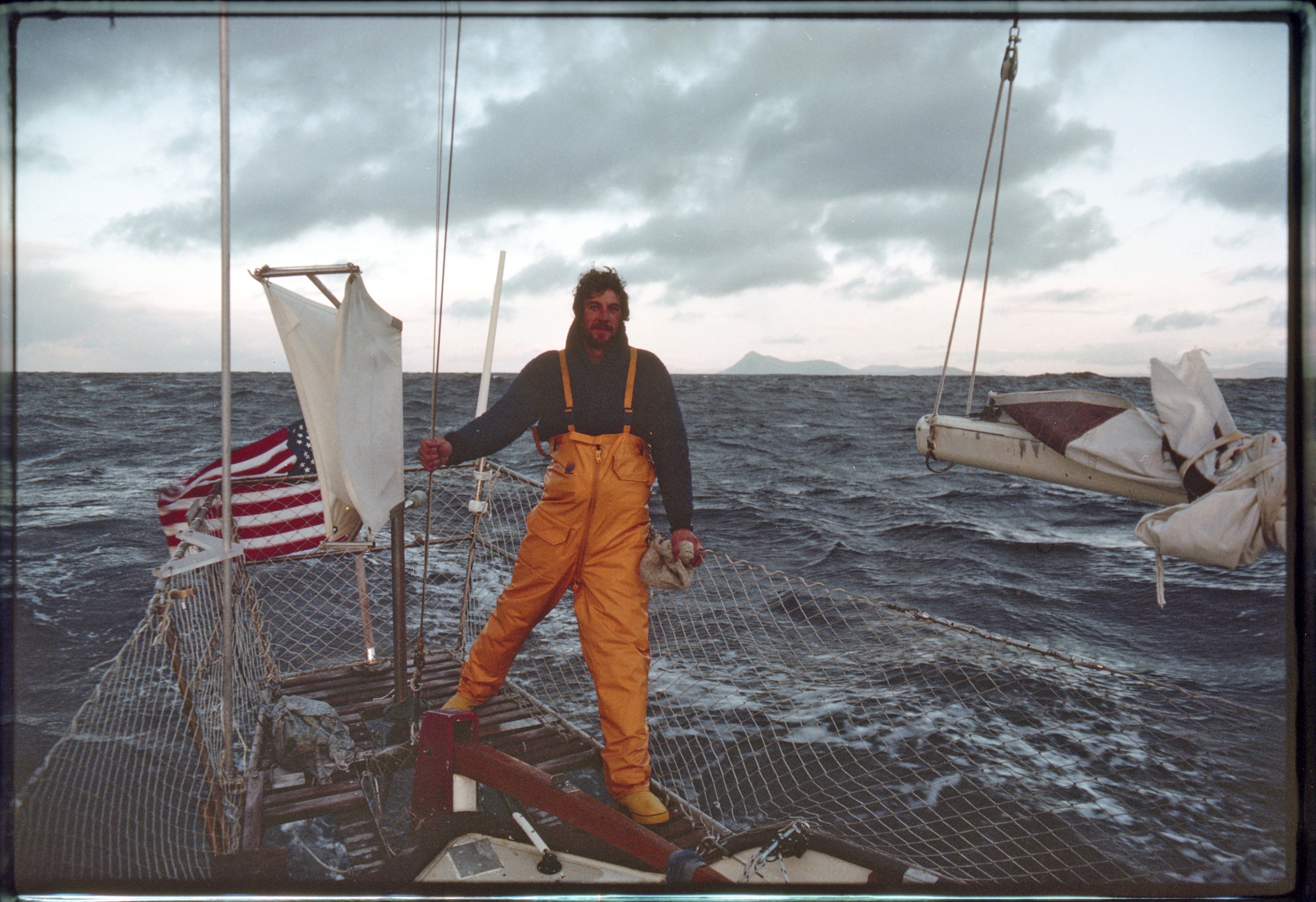

At 0330 on February 25 I was awakened by Rob. “Congratulations, Maxwell.” I went out on deck, and saw, darkening the sky to our north, a headland: Cape Horn. We drifted by in a 10-knot breeze, with only a trysail up to still the rocking. The sun soon followed to light up this magnificent cape and the rugged terrain behind.

I tried to imagine what kinds of conditions had greeted sailors here over the centuries. It was for us the first sight of land in so many days. I wondered for how many men this was their last sight. How many died here in sight of her indifferent gaze? I knew our calm seas and light winds today were almost a cruel mockery of what others had faced here.

We turned Christopher Robin north and scooted on toward the Falklands. As we did, I looked back a last time to let the haunting image of Cape Horn emblazon itself in my soul. She will always be there, and in my mind, so will I.